If you’ve been a comics fan for any length of time, you’re probably familiar with the concept of the “Silver Age of Comics” — a hallowed era of comic book history extending from (probably) 1956 to (maybe) 1970. You may even have an image that comes to mind if someone says a phrase like “the Silver Age Flash”, or “the Silver Age Thor”, visualizing an emblematic artistic interpretation of a character that flourished in that era. But even if you’re as old and grizzled a fan as this blogger, you may find yourself hesitant, and even confused, should someone ask you to visualize “the Silver Age Batman.”

That’s as it should be, frankly, because the decade-and-a-half period we call the Silver Age encompassed a number of distinct interpretations of Batman, all involving different approaches to depicting (in story, as well as art), the character and his world. My own, personal inclination is to identify the “Silver Age Batman” with editor Julius Schwartz’ “New Look” version of the character, introduced in 1964. And I can make a strong case for that, I believe, based on Schwartz’ role in the Silver Age revival of superheroes like Flash, Green Lantern, Hawkman, and the Atom — said revival being one of the main markers of the era. But, when it comes right down to it, my inclination probably owes at least as much to the fact that that version of Batman happens to be the one I first encountered as a reader, way back in 1965.

If I’m going to be truly objective, however, I have to admit that the phrase “Silver Age Batman” encompasses all the versions depicted in the gallery below — from Sheldon Moldoff’s early-Sixties science-fiction adventurer, to Carmine Infantino’s more grounded mid-Sixties crimefighter, to Neal Adams’ late-Sixties revival of Gotham City’s “dark knight” — the version which, allowing for some modification and evolution over the decades, still dominates today:

And even in August of 1966 — fifty years ago, at this writing — there wasn’t just one, singular vision of Batman. Julius Schwartz was the editor of the Caped Crusader’s two primary titles, Batman and Detective, and also supervised his appearances in Justice League of America. But Batman was too important a character to be limited to appearances in just those three books, especially in the summer of 1966 — the peak of “Batmania”. Thus, the hero not only continued to be featured in World’s Finest (where he’d been co-starring with Superman since 1941), as edited by Mort Weisinger, but also began turning up frequently in The Brave and the Bold, edited by George Kashdan, which had made a transition from being a tryout to a team-up book over the last couple of years.

July 30, 1966 saw the premiere of the motion picture version of the Batman TV series, as heralded in full-page ads in DC’s comics published at and around that time (including the ostensible subject of this post, Brave and the Bold #68):

It’s instructive, I think, to look at the comics featuring Batman that hit the stands in July and August that year, and to consider how each of the different books’ editors — Schwartz, Weisinger, and Kashdan — chose to capitalize (or not) on the character’s white-hot popularity, and the attendant vogue for the “camp” approach taken by the TV series and movie:

The cover of Batman #184 plays up the Bat-Signal and Hot-Line, two story elements that got a lot of regular attention on the television show, and also features rather breathless copy that evokes the show’s over-the-top voiceover narration by producer William Dozier. Meanwhile, Detective #355’s cover nods to the TV Robin’s well-known habit of speech with its “Holy gallows!” blurb. And Julius Schwartz’ third Batman-featuring title of July, JLA #47, simply and shamelessly masquerades as a full-on Batman comic book, with the figure of the Caped Crusader dwarfing all the other heroes on the cover (despite his relatively minor role in the story itself). Finally, there’s Mort Weisinger’s World’s Finest #160, which at first glance might not seem to be catering to the TV audience at all. It must be noted, however, that this was the first issue to add Batman’s and Superman’s logos to the cover — and, breaking with the long-established tradition of the series’ story-opening splash pages, Batman was given top billing over Superman — probably for the first time ever.

Moving from July into August — both Batman and World’s Finest offered 80-Page Giant reprint collections, which I’ve posted about in recent weeks. Detective? Well, we’re going to have to save that one for the next post, sorry. And Justice League of America skipped a month. So, save for the aforementioned issue of Detective, there was but one “new” adventure of Batman hitting the spinner racks in August. The Brave and the Bold didn’t ship an issue in July, but George Kashdan and his creative team more than made up for that with issue #68. Remember that cover? If you’ve already forgotten (how could you ever?), scroll back up to the top of this post — or you can just click here.

Got it? Bask in its glory for another moment or two, then let’s move on into the issue.

We last checked in on Brave and the Bold with issue #64, which featured Batman’s second co-starring turn in the book. That issue might have hit the stands a little less than a month before the premiere of the Batman TV series, but it served early notice that BatB’s regular scripter Bob Haney was prepared to approach Batman somewhat differently than Schwartz’s mainstay writers like Gardner Fox and Robert Kanigher. Indeed, Haney gave Batman dialogue unlike anything fans had ever read coming from the hero’s mouth before. (Here’s just one example, but it’s my favorite: “Marcia… baby… how could you do it? You set me up and I fell for the neatest, crummiest, double-cross since Delilah trimmed Samson!”)

By issue #68, Haney had one more Batman-featuring story under his belt (issue #67, co-starring the Flash), and seemed, if anything, even more confident in his somewhat unorthodox approach to the character. Of course, by now he had the success of the TV show to serve as proof that a less staid-and-serious attitude towards the material could work with audiences, and in his first panels following the introductory splash page, he hit the ground running:

(As an aside — Robin was always “away on on a Teen Titans mission” or otherwise indisposed when Batman teamed up with other heroes in Brave and the Bold. Even though Robin was appearing regularly in World’s Finest, as well as in Batman and Detective, the Boy Wonder never showed up for these BatB adventures. Was the character off-limits somehow to Kashdan and Haney, or did they just not want to fool with him here, in addition to Teen Titans, which they also edited and wrote, respectively? I honestly have no idea.)

Unheedful of the importunings of the story’s anxious narrator, Batman attempts to tune in Commissioner Gordon on the Batmobile’s in-dash closed-circuit television:

After quickly working out the riddle, Batman arrives at the Diamond Exchange just in time to foil the Riddler’s robbery — or so he thinks. The costumed criminal tosses a gem out the window, and Batman catches it — but when he finds it heating up in his hand, he throws it away just before it explodes, releasing a strange gas. The Riddler escapes, and Batman resumes his patrol, wondering what that business was all about:

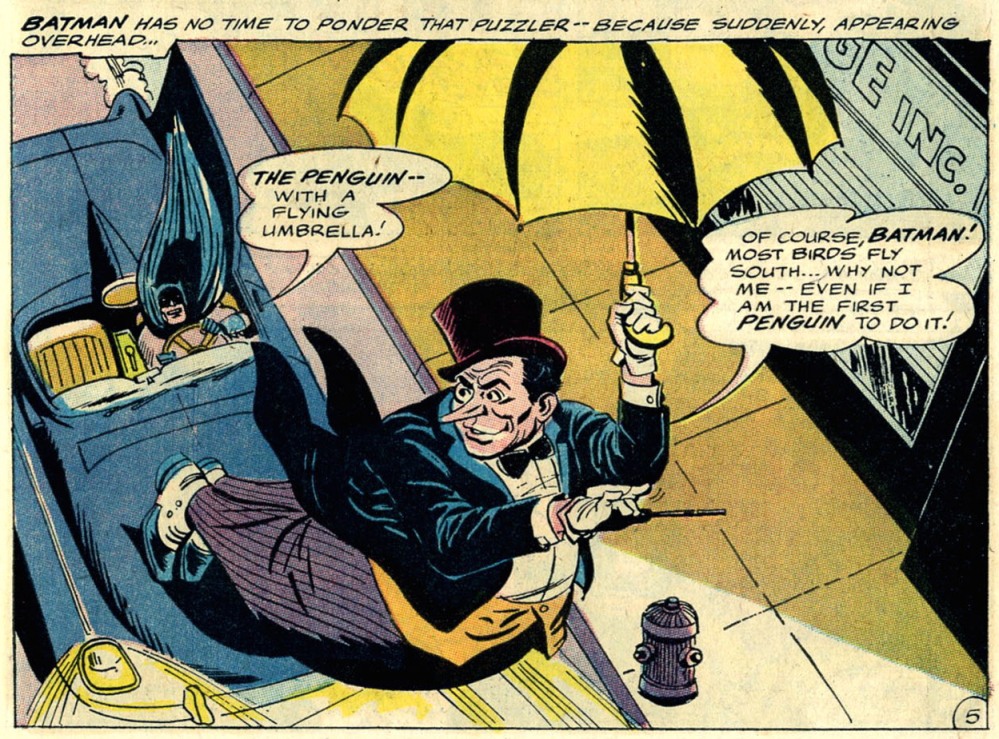

Batman pursues this second arch-foe of the evening to the Gotham City Museum, but when he attempts to apprehend the Penguin, the villain sends a crow flying at him. Seeing a strange dust flying from the black bird’s feathers, Batman ducks out of the way, but once again, his enemy escapes — leaving the Caped Crusader to ponder yet another mystery. “Something’s cooking,” he muses, “– and it’s not blackbird pie!”

The Joker tells Batman that he’s booby-trapped the Batmobile. Batman expects to foil him by flipping the vehicle’s Anti-Booby-Trap Circuit (seriously — there’s a label next to the button, and everything) — but, wouldn’t you know it, that’s where the booby trap is!. The button releases a gas, which incapacitates our hero, who runs the Batmobile into a utility pole. Part 1 closes as the Batman lies sprawled in the driver’s seat, laughing uncontrollably. That scenario is likely to remind many modern readers of the effects of the Clown Prince of Crime’s deadly “Joker venom” — but as the opening scene of Part 2 makes clear, there’s something else going on this time (unsurprisingly — for though the Joker had killed people with toxins in his very first appearance in 1940’s Batman #1, and would do so again in the future, in the 1960s he wasn’t so overtly murderous):

As quickly becomes apparent, this thing-that-was-Batman has criminal proclivities, as well as an unsettling sense of humor — and, most dangerously of all, uncanny chemical-based superpowers:

A number of online resources refer to Bat-Hulk as a “Hulk parody”, and I suppose he could be — Marvel Comics’ Hulk had been around since 1962, after all — but he doesn’t really resemble the Marvel character that much in his body shape, not to mention his skin color (neither green nor gray) — plus, Marvel’s Hulk has never demonstrated any chemical-manipulating abilities. Plus, “hulk” isn’t really that uncommon a word, anyway — and in this case, it’s actually pretty descriptive. Considering all this, unless someone can direct me to a confirming quote from Haney or one of his collaborators on the topic, I’d say that the claim of an intentional Marvel-Hulk parody remains speculative.

What can’t be denied, however, is that the character concept falls right in line with the “bizarre transformations” tradition of the pre-“New Look” Batman era, in which the Caped Crusader frequently found himself mutated into some strange new form, ranging from a King Kong-like ape monster to a, well, baby. This might be considered ironic, considering that the Batman TV series (the approach of which seems to be setting the model for Haney’s story) is widely considered to have been inspired by the “New Look” Batman comics that were current when producer Dozier first got the idea for his television adaptation; however, as comics historian Arlen Schumer has recently pointed out, it seems quite likely that Dozier may have been just as influenced by reprints of stories from the preceding, Jack Schiff-edited era. If that’s true, then perhaps the main reason why we didn’t see Adam West transformed into, say, Zebra Batman was the show’s limited special effects budget.

What can’t be denied, however, is that the character concept falls right in line with the “bizarre transformations” tradition of the pre-“New Look” Batman era, in which the Caped Crusader frequently found himself mutated into some strange new form, ranging from a King Kong-like ape monster to a, well, baby. This might be considered ironic, considering that the Batman TV series (the approach of which seems to be setting the model for Haney’s story) is widely considered to have been inspired by the “New Look” Batman comics that were current when producer Dozier first got the idea for his television adaptation; however, as comics historian Arlen Schumer has recently pointed out, it seems quite likely that Dozier may have been just as influenced by reprints of stories from the preceding, Jack Schiff-edited era. If that’s true, then perhaps the main reason why we didn’t see Adam West transformed into, say, Zebra Batman was the show’s limited special effects budget.

But back to our story: After eluding the police, Bat-Hulk unexpectedly transforms back into Batman — however, the Caped Crusader knows that doesn’t mean that he’s out of the woods (metaphorically as well as literally):

Who’s he gonna call? None other than the world’s richest man (and scientific genius), Simon Stagg — who also happens to be the employer of “the world’s most fantastic hero” — Metamorpho!

As regular readers of this blog may remember, I’d met Metamorpho (aka Rex Mason) when he guest-starred in Justice League of America #42 — so when I first read this story in August, 1966, I was already familiar with the character’s power, personality, and origin. However, even though I’d enjoyed Metamorpho in that issue, I hadn’t taken the plunge and picked up an issue of the Element Man’s own book — thus, this was my first encounter with his supporting cast, who in addition to the manipulative and morally ambivalent Stagg included the genius tycoon’s daughter (and Rex’s girlfriend) Sapphire, as well as his Neanderthal servant, Java.

(Bob Haney, incidentally, was the co-creator of Metamorpho, and the regular scripter on his ongoing series [also edited by George Kashdan]. It’s easy to see how the writer could have felt that his unconventional, half-parodic approach to superheroic adventure in that book would fit well with the over-the-top take on Batman and his world he was going for in this story.)

After making his way to Stagg’s mansion, Batman explains the situation to all those present, and then gratefully accepts Stagg’s offer of help:

Metamorpho attempts to subdue Bat-Hulk, but “great chemical powers” notwithstanding, the creature manages to escape…

It’s worth noting here, I think, that this story marks the first time that the Joker, the Penguin, and the Riddler had ever teamed up together… in comics. As I and probably most other readers would have known when  this

this  book came out, the three “weirdos”, joined by Catwoman, had already combined forces to plague Batman and Robin in the new Batman movie. Even before that, two of the three (Joker and Penguin, again joined by Catwoman) had appeared in Winston Groom’s prose paperback novel, Batman vs. 3 Villains of Doom, which had been published earlier that year, and which my younger self had happily purchased and read. I think it still seemed like a big deal when I saw these three characters together in this story, however. The “big four” Batman villains (as I’d come to think of them) didn’t appear in Batman and Detective comics nearly as often as they turned up on the TV show, and for more than one of them to appear in the same comic book story was something I hadn’t seen before. (For the record, the idea of the Joker and Penguin teaming up as a duo went back quite a ways, to 1944’s “Knights of Knavery” [Batman #25]}. The Riddler, on the other hand, had never teamed up with any other Bat-villain before, in large part because he’d barely been around before — in fact, though he’d been introduced in 1948, BatB #68 was only the character’s sixth appearance in any comic, ever. As I discussed in my Batman #179 post this past January, the Riddler wasn’t a big deal until the TV series [and, more specifically, actor Frank Gorshin] made him a star.)

book came out, the three “weirdos”, joined by Catwoman, had already combined forces to plague Batman and Robin in the new Batman movie. Even before that, two of the three (Joker and Penguin, again joined by Catwoman) had appeared in Winston Groom’s prose paperback novel, Batman vs. 3 Villains of Doom, which had been published earlier that year, and which my younger self had happily purchased and read. I think it still seemed like a big deal when I saw these three characters together in this story, however. The “big four” Batman villains (as I’d come to think of them) didn’t appear in Batman and Detective comics nearly as often as they turned up on the TV show, and for more than one of them to appear in the same comic book story was something I hadn’t seen before. (For the record, the idea of the Joker and Penguin teaming up as a duo went back quite a ways, to 1944’s “Knights of Knavery” [Batman #25]}. The Riddler, on the other hand, had never teamed up with any other Bat-villain before, in large part because he’d barely been around before — in fact, though he’d been introduced in 1948, BatB #68 was only the character’s sixth appearance in any comic, ever. As I discussed in my Batman #179 post this past January, the Riddler wasn’t a big deal until the TV series [and, more specifically, actor Frank Gorshin] made him a star.)

But returning again to our story… this cabal of costumed crooks doesn’t get to gloat over its good fortune for long:

Great eagles save us! Yes, it seems like the monstrous Bat-Hulk has the upper hand — but the tables are quickly turned mere moments later, as the “chemical pheeenom” transforms into Old Cape-and-Cowl once again:

The “switch on the switch on the switch”? Say, which switch is which? (For additional amusement, try reading that last caption in William Dozier’s TV narrator’s voice.)

Wouldn’t you know it, though — this change lasts only long enough to gin up a little reader suspense between Parts Two and Three — for just as soon as we turn to that “3rd page following”, Batman turns back into Bat-Hulk. And this time it’s permanent, as he tells the three Bat-villains: “Batman’s gone for good!… He’s dead! But Bat-Hulk lives! Haw! Haw!”

Metamorpho and company conveniently happen upon Bat-Hulk and his new teammates as they’re robbing a bank, using the Batcopter (here called the “Flying Bat-Cave”). Unfortunately, Bat-Hulk cleans the Element Man’s clock again, leaving him literally in pieces in the gutter, and the crooks escape with their loot. Simon Stagg re-assembles Metamorpho with the help of a jolt of electricity, and then:

(Of course, Commissioner Gordon has taken the time during this crisis to modify the Bat-Signal! That veteran cop understands how things work in his city.)

However, after the gang catches up to their quarry, it doesn’t look like things are necessarily going to go any better for Metamorpho than in his last two battles with Bat-Hulk. But then, as they’re sparring across Gotham’s rooftops, the creature grabs what Rex takes for a TV antenna, and Mother Nature steps in:

“Be seeing you on the TV, pal!” A fitting final remark for a story that took its cues from the Batman TV series as much, if not more, than any other Batman comic book tale ever did (or until 2013, at least).

I have to confess that I approached this story with some trepidation before beginning to work on this post. I’d decided months ago that I wanted to blog about it, but I hadn’t read the story in decades, and the vague memories I had of it suggested to me that it had never been one of my favorites. I was prepared to declare it the most egregious example of DC’s attempts to capitalize on the popularity of the Batman TV series and its vaunted “camp” aesthetic, and to judge it one of the worst comic books of its time. Imagine my surprise, then, when I re-read the story and found that I… kinda enjoyed it.

Sure, Haney’s script is over-the-top, but probably pretty much in tune with the work he was doing on Metamorpho (which I must admit, in the interest of full disclosure, I’ve had little direct experience of as a reader). His plot zips along and is actually pretty solidly constructed (well, until you get to the “lightning strike” climax, anyway). And the uncredited art by Mike Sekowsky (pencils) and Mike Esposito (inks) serves the rollicking action of the story quite well. It’s certainly livelier than the competent but dull work that Sheldon Moldoff was regularly turning in for Batman and Detective at the time.

So why, prior to my recent re-reading, did I not remember this story more fondly? I can only speculate, but I have an idea that I just didn’t like “Bat-Hulk” — either conceptually, or visually. For whatever reason, the whole “bizarre transformations” shtick never appealed to me much as a kid. I pretty much avoided the “Red Kryptonite” stories in Weisinger’s Superman books for that reason (not to mention the “Lois Lane’s Super-Brain” and “Giant Turtle Man” Jimmy Olsen type of material). There’s probably a deep-set psychological reason why my younger self found such tales unsettling, but for now I’m content to say that they just didn’t float my boat. At the age of 59, however, I seem to have outgrown that aversion (though many of my other youthful predilections remain intact).

I began this post with a discussion of the many faces of “the Silver Age Batman”, and I’d like to close with a consideration of the role that The Brave and the Bold played in the Caped Crusader’s transition to a more-or-less consistent characterization — the “grim avenger of the night” most familiar to readers and moviegoers of today — at the end of that era.

As I’ve previously noted, when BatB #68 came out, the book was in transition. Originally the home for several ongoing historical adventure series, the title later became first a book for trying out new concepts (during this period, it premiered Justice League of America and Hawkman), then, under George Kashdan, a mix of tryouts with team-ups. By August, 1966, the book was all team-ups, but Batman was featured only in some of them. That would change less than a year later, with issue #73, featuring Aquaman and the Atom, being the last issue not to feature the Caped Crusader. The very next issue, published in August of 1967, featured Batman co-starring with the Metal Men — and Batman would continue to co-star, without interruption, for another126 issues, through #200, published in March, 1983.

The man who would write all but a handful of those issues, Bob Haney, was already well established as the book’s regular scripter in August, 1967; but he continued to work with a varied roster of artists on the book, and with the June-July, 1968 issue he got a new editor, when Murray Boltinoff, who’d worked with Kashdan on a few of the earliest team-up issues, was brought back in on the series. Then, just two months later, another significant change occurred, as Boltinoff’s second issue featured the first interior art on the series by a rising young artist who’d already done a couple of BatB covers for Kashdan — a fellow named Neal Adams.

The Brave and the Bold #79’s “Track of the Hook” wasn’t the first story featuring Batman to be illustrated by Adams — that would be World’s Finest #175’s “The Superman-Batman Revenge Squads!” — but it was the story in which he first truly began to develop his own visual interpretation of the character, rather than just following a writer’s lead. This first issue was succeeded by seven more illustrated by Adams, all scripted by Haney. By the time Adams’ run on the book was through, the editor of the “real” Batman titles, Julius Schwartz — who, by all accounts, hadn’t been particularly keen when Adams had first asked him about working on the character — was impressed enough to put Adams on Batman and Detective, pairing him with new writers such as Dennis O’Neil — and the rest, as they say, is history.

The Brave and the Bold #79’s “Track of the Hook” wasn’t the first story featuring Batman to be illustrated by Adams — that would be World’s Finest #175’s “The Superman-Batman Revenge Squads!” — but it was the story in which he first truly began to develop his own visual interpretation of the character, rather than just following a writer’s lead. This first issue was succeeded by seven more illustrated by Adams, all scripted by Haney. By the time Adams’ run on the book was through, the editor of the “real” Batman titles, Julius Schwartz — who, by all accounts, hadn’t been particularly keen when Adams had first asked him about working on the character — was impressed enough to put Adams on Batman and Detective, pairing him with new writers such as Dennis O’Neil — and the rest, as they say, is history.

Of course, The Brave and the Bold went on much as it had before, with Haney continuing to go his own idiosyncratic way as scripter; but the times were changing, and before very long at all, Adams’ approach to Batman became the standard for the character, at least visually. Batman might appear in the daytime more in BatB than he did in his other titles, but the long-eared, billowing-caped star of the book was still the Darknight Detective of Adams’ design, even if now illustrated by others (most frequently, Jim Aparo — as on the 1973 cover depicted at right, Aparo’s first of many for the book).

Of course, The Brave and the Bold went on much as it had before, with Haney continuing to go his own idiosyncratic way as scripter; but the times were changing, and before very long at all, Adams’ approach to Batman became the standard for the character, at least visually. Batman might appear in the daytime more in BatB than he did in his other titles, but the long-eared, billowing-caped star of the book was still the Darknight Detective of Adams’ design, even if now illustrated by others (most frequently, Jim Aparo — as on the 1973 cover depicted at right, Aparo’s first of many for the book).

But now, of course, we’re no longer talking about the Silver Age, but rather “the Bronze Age Batman” — and that’s a discussion that should probably wait for a future post. So, check back with me in about… oh, let’s say five years, OK? See you then.

Great post. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Flying Batcave, introduced in Detective Comics #317, was not the same vehicle as the Batcopter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was wrong. The Flying Batcave first appeared in Detective #186. Its second appearance was in #317.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bob, I was using the term “Batcopter” more generically — probably under the influence of the “Batcopter” article on Wikipedia that lists the Flying Batcave as one of several models — but I take your point. 🙂

LikeLike