The subject of today’s post has the distinction of being the first Marvel Comics “first issue” I ever purchased. That may actually be somewhat less of a big deal than my putting it that way makes it sound, since, way back fifty years ago in May, 1968, I’d only been buying Marvel’s books regularly since the beginning of the year — and also because prior to January, 1968, launches of brand-new Marvel comics were pretty rare birds.

As has been discussed previously on this blog, from 1957 up through the end of 1967 the number of titles that Marvel was allowed to publish was tightly controlled by their distributor, Independent News — which just so happened to be owned by National Periodical Publications, aka DC Comics, Marvel’s largest competitor. Although Marvel’s sales ultimately contributed to DC’s bottom line, the latter publisher had an obvious interest in keeping Marvel from getting too big, and potentially cutting into their own comic book sales. As a result, the number of first issues published by Marvel from 1965 through 1967 (excepting annuals and reprint titles) can be counted on the fingers of one hand*.

Of course, even when Marvel began to dramatically expand its line in early ’68, following the re-negotiation of its distribution deal, not every “Big Premiere Issue” was an actual “number one”. In splitting their three double-hero comics — Tales of Suspense, Tales to Astonish, and Strange Tales — into six solo titles, Marvel had three of the new series continue with their “parent” titles’ numbering. So, over the course of the first few months of the year, comics buyers had the opportunity to buy Iron Man #1, Sub-Mariner #1, and Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. #1 — and also Captain America #100, Hulk #102, and Doctor Strange #169.

Not that my ten-year-old self deigned to plunk down twelve cents for any of them. As noted earlier, I didn’t start buying Marvel comics on a regular basis until January, 1968 (though I’d bought one single Marvel book prior to that, the previous summer), and I was being cautious (in hindsight, way too cautious). By May, however, I was ready to take the plunge and take a chance on something new — even something that cost not twelve, but a whole twenty-five cents. In making that decision, I was almost certainly influenced by this full-page house ad running in other Marvel comics that month:

How the heck could I pass on that? Unlike the six other Marvel heroes who’d gotten their own books this year, Silver Surfer #1 wouldn’t be continuing storylines that had started in the headliner’s previous home base — it would be starting from scratch, and with an origin story to boot! Plus, the origin of the Watcher! And while the “king-sized” format did make the book a more expensive choice, it also helped to set the book apart from Marvel’s other offerings, and made its debut seem like a special event. (It did for my ten-year-old self, at any rate.)

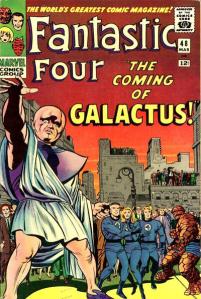

Did I even know who the Silver Surfer was, at this point? I’m pretty sure I did. I was regularly watching the Fantastic Four animated cartoon series that had started airing on Saturday mornings the previous fall, and that show’s adaptation of the FF comic book’s “Galactus Trilogy”, the 1966 storyline that had introduced the Surfer to the world, had aired

Did I even know who the Silver Surfer was, at this point? I’m pretty sure I did. I was regularly watching the Fantastic Four animated cartoon series that had started airing on Saturday mornings the previous fall, and that show’s adaptation of the FF comic book’s “Galactus Trilogy”, the 1966 storyline that had introduced the Surfer to the world, had aired  in December. And even though I wasn’t yet reading the Fantastic Four comic, thanks to Marvel’s “Bullpen Bulletins” pages and house ads I was nevertheless aware that both the world-devouring villain Galactus and his former herald, the Surfer, were currently appearing in a storyline that had been running in that book for several months, and that would in fact conclude in FF #77, published the same month as Silver Surfer #1. In other words, I was probably about as primed to read and enjoy this “All-New Book-Length Marvel Epic!” as any Marvel newbie who’d never read a story about the character before could be.

in December. And even though I wasn’t yet reading the Fantastic Four comic, thanks to Marvel’s “Bullpen Bulletins” pages and house ads I was nevertheless aware that both the world-devouring villain Galactus and his former herald, the Surfer, were currently appearing in a storyline that had been running in that book for several months, and that would in fact conclude in FF #77, published the same month as Silver Surfer #1. In other words, I was probably about as primed to read and enjoy this “All-New Book-Length Marvel Epic!” as any Marvel newbie who’d never read a story about the character before could be.

And when I opened up the cover and scanned the credits on the first page, I would have recognized the names of the two creators who “proudly presented” the tale — Stan “the Man” Lee, who wrote the two Marvel books I was following most closely (Amazing Spider-Man and Daredevil) and edited everything else, and John “Blood ‘n’ Guts” Buscema, the penciler of Avengers:

The name I didn’t see anywhere on that opening splash page — and might have expected to, if I’d been reading Marvel comics for longer than a few months — was that of Stan Lee’s Fantastic Four collaborator, Jack Kirby. But, newbie that I was, I didn’t know that Kirby had drawn every single Silver Surfer appearance from his debut in FF #48 up until now (with the exception of a guest shot in the Hulk’s strip in Tales to Astonish #93, drawn by Marie Severin) — including the character’s only solo appearance to date, in a back-up story published in FF Annual #5. Nor did I have any idea that Kirby had, in fact, created the Surfer all by himself, without input from Lee, for that 1966 FF issue — though, to be fair to my younger self, hardly anyone else outside of Marvel’s staff knew that, either.

It’s frankly impossible to write about Silver Surfer #1 without discussing Jack Kirby (at least to write responsibly about it), and I have no intention of doing so. But because it’s a complex topic, and also because my ten-year-old self barely knew who Kirby was when he first read this comic book in May of ’68, I’m going to defer most of that discussion until later in the post. Don’t worry, though; we’ll get there, eventually.

For now, however, we’ll jump right in to the opening-scene action served up by Lee and Buscema, starting on page two:

The Surfer extricates the unconscious but unharmed astronaut — identified in dialogue as “Col. Jameson” (and while he’s not specifically said to be Col. John Jameson, the son of Daily Bugle publisher and number one Spider-Man hater J. Jonah Jameson, it seems a safe bet that such is Lee’s intention) — and delivers him to safety on a nearby aircraft carrier. Unfortunately, the military consider the Surfer to be a threat, and scramble jets to pursue him:

After making his supersonic escape, the Surfer proceeds to buzz “almost every capital on Earth” for some reason, though we’re only shown him streaking through the skies of Moscow and Beijing. The two communist world powers fire missiles at him, ineffectually, in a two-panel sequence that doesn’t seem to serve any purpose other than allowing the creators to take some gratuitous potshots at America’s Cold War rivals.

The following page brings us to a scene depicting some lovely (if rather oddly colored) landscapes, strikingly rendered by Buscema and inker Joe Sinnott, as well as the first of our protagonist’s ruminative soliloquies:

Speeches such as this one, in which the Surfer expresses his bewilderment and/or sorrow at the behavior of humanity, while also bemoaning his own exile upon Earth, would soon prove to be the heart of this Silver Surfer series. Kirby’s visualization of the character as a pristine, gleaming, godlike figure had inspired Lee to instill him with both a purity of spirit and a nobility of mind (and speech) which served to distinguish him from any other Marvel superhero.

The soliloquy leads into the first of several flashback sequences which will, over the course of the story, reveal the full origin of the Surfer, as promised in the story’s title:

I think it’s worthwhile to note here that the information provided in this scene, as well as in every other scene relating to Zenn-La, Norrin Radd, etc., was as new to veteran Marvel readers in May, 1968 as it was to my newbie self. In none of the Surfer’s previous appearances had any details of his life before becoming Galactus’ herald been revealed; indeed, there’d been little if any indication that he had ever had any other life.

Over the next few pages, the Surfer tells us more of the discontent he felt as Norrin Radd, and how it set him apart from his fellows. The Surfer describes Norrin’s visit to the Museum of Antiquity, where through a sort of advanced virtual reality technology, he could witness the full history of his planet as though he were present for the events — a rather clever device that allows Lee and Buscema to give us that background without turning the Surfer/Norrin into a mere narrator.

We learn that the people of Zenn-La had experienced a million year long Age of Warfare, which was followed by a ten-thousand year long Golden Age of Reason. The Zenn-Lavians had achieved a lasting peace, reached new heights of learning and wisdom, and then had proceeded to fearlessly explore the cosmos — until, in Norrin’s words: “We had gone too far — seen too much! And then — we no longer cared!” The people of Zenn-La abandoned their spacefaring ways and returned to their homeworld, never to venture forth again.

Back in the present day, where the Surfer has touched down in the Himalayas, his reverie is interrupted when he is attacked by a small band of Yetis, aka Abominable Snowmen. They are of course no match for him, and while the brief sequence allows the storytellers to showcase some of the Surfer’s powers (including strength, durability, and mental control over his board), it does little to advance the plot.

The brief skirmish with the Yetis leads the Surfer to recall some of his other conflicts with Earthlings, including a couple of such that he had attempted to befriend:

The Surfer goes on to describe how Doom betrayed his trust and stole his powers, but doesn’t detail how he (or the world) got out of that mess — which my younger self found incredibly tantalizing, back in 1968. Some months later, the issues of Fantastic Four that told the full story (#57 – #60) would be among the very first back issues I ordered through the mail.

Still soaring over the Himalayas, apparently, the Surfer notices some half buried ruins on a mountainside, and decides to investigate — and, naturally, takes the opportunity to deliver another mournful soliloquy as he does so:

The story now returns to the Surfer’s memories of his last days on Zenn-La, where it’ll remain for most of the rest of the tale:

Norrin went on to grouse about how how awful it was that the Zenn-Lavians didn’t have to work to gain knowledge (they absorbed it from “hypno-powered study cubes”) or material things (they could make anything they wanted using “an inexpensive cyberno-materializer“). And then…

Norrin somehow sensed that his moment of destiny was upon him — that his own fate was “inexorably linked with the unknown invader from space!” Meanwhile, Zenn-La’s leaders, in obedience to their “infallible computers“, deployed the “Weapon Supreme” against the rapidly approaching vessel. Unfortunately, the weapon’s power wreaked massive damage on Zenn-La itself, while the invader’s ship completely escaped harm by temporarily slipping into the Fourth Dimension.

Determined to find others who’ll make a last stand with him, Norrin left Shalla and went out into the ruined city. He happened to find someone he recognizes as a member of the Council of Scientists — and pleaded with the man to build him a spaceship so that he could approach the invader and, perhaps, convince them to spare Zenn-La. Though the scientist believed the cause was hopeless, he was nevertheless moved by Norrin’s zeal, and agreed to help him:

As I mentioned earlier, I’m pretty certain that I already knew Galactus from his appearance on the ABC-TV Fantastic Four cartoon series — but the spectacular full-page Buscema-Sinnott splash with which he made his entrance here was still jaw-dropping. Meanwhile, Lee’s dramatic prose — which achieves an almost poetic effect through the repetition of “Galactus!” in Norrin’s interior speech, — played at least an equal role in selling the scene.

This multi-page sequence, featuring Norrin Radd’s fateful bargain with Galactus and his subsequent transformation, knocked me out in 1968, and remains powerful today, fifty years later. Buscema’s drawing on these pages is some of the most graceful and imaginative work he’d ever do for Marvel, in my opinion.

The scene’s effectiveness is undercut just slightly, perhaps, by the dialogue Lee provides Galactus in the next panel:

Buscema’s rendering of Norrin Radd’s transformation on page 32 suggests that Galactus entirely rebuilt the Zenn-Lavian from the atomic level on up — but the dialogue refers instead to his body being “completely encased in a life-preserving silvery substance” — which sounds like he simply dipped Norrin as-is in silvery goo, in a process akin to dipping a strawberry in melted chocolate. That’s somewhat at odds with what our eyes have just shown us (along with simply being less, well, awesome), and while I don’t recall the discrepancy fazing my ten-year-old self in the slightest in ’68, it irritates me just a bit today.

But only a bit… Anyway, moving on, we see Galactus complete the creation of his herald with the creation of the vehicle he’ll use to traverse the cosmos, aka his board:

(Why did the Devourer of Worlds provide his new herald with a vehicle that so closely resembles a piece of sporting equipment from Earth? I dunno. Maybe surfing was an especially popular sport on Taa?)

Before the newly christened Silver Surfer could go hunting for an uninhabited planet for his new boss to much, he had a stop to make:

It’s unfortunate that Lee hasn’t gone to the trouble of giving Shalla Bal much of a personality — or any individual qualities at all, really, beyond her physical beauty and evident devotion to Norrin Radd — to help us understand why the Surfer cares so much about her that their separation feels like a tragedy. It’s not so much a problem in this story, where Shalla only appears in two scenes, and the reader is probably willing to take Lee’s word regarding the greatness of their love at face value. It does become more problematic in later issues of the series, however, as Lee and Buscema make Shalla Bal a recurring character, and her one-note characterization eventually becomes grating.

The Surfer’s “voiceover” narration now turns to his years of wandering the spaceways (interestingly, we don’t actually see him fulfill his initial charge of locating a suitable replacement for Zenn-La, though it’s safe to assume he was successful):

And then, at last, the narrative reaches the point at which the longtime Marvel comics reader originally “came in” — the point at which the Surfer entered the storyline of Fantastic Four #48. Unfortunately, the two strands of story don’t knit together quite as tightly you might expect, considering that they were scripted by the same writer, and that the original story was only two years old when this one was published. The seams clearly show, in ways that we’ll discuss in more depth a little further on.

These final couple of pages feel slightly rushed, especially in comparison to how the story has been paced up to this point, with time allotted for the Surfer to spar with Yetis and explore buried ruins between flashbacks. (The semi-apologetic footnote from “Squeamish Stan” at the bottom of page 37 may acknowledge this, if obliquely.) Working “Marvel style”, Buscema would have had the primary responsibility for the pacing; and since I’ve never read that he ever started drawing a story before having read the plot all the way through (unlike Gene Colan, for example), I’m inclined to think that perhaps the story was originally slated to run a couple of pages longer, and the artist had already completed penciling the majority of pages when the decision was made to cut its length. This is all just speculation on my part, however.

That end-of-the-race bobble and other minor flaws aside, however, “The Origin of the Silver Surfer” is a fine piece of storytelling, with Lee, Buscema, and Sinnott all working at or near the top of their game. Taken purely on its own terms, it still holds up today as one of the most memorable comic book stories of 1968 — a year in which a lot of great comics were published.

Unfortunately, it’s not really possible — or even advisable — to take the story purely on its own terms. And the reason for that is, of course — Jack Kirby.

But before we get into all that, we need to take a look at the rest of the contents of Silver Surfer #1 — specifically, the second new story that filled out the double-sized issue, “The Wonder of the Watcher”:

It was unusual, in 1968, for Marvel to produce a double-sized format comic on a regular schedule, even a bi-monthly one — the only other one they were doing at the time was the humor anthology Not Brand Echh, which had just been converted from a 12-cent to a 25-cent comic the previous month, with issue #9. That may be one reason that Stan Lee hedged his bets a little with Silver Surfer‘s “co-feature” starring the Watcher. Although the art was all-new, the stories themselves were reworkings of tales that had been  published years earlier. That included this first installment which, much like the lead story of this issue, presented the origin of its star through a flashback sequence narrated by that character. The thirteen-page “The Wonder of the Watcher!” — scripted by Lee, penciled by Gene Colan, and inked by Syd Shores — was, therefore, a direct adaptation of the five-page “The Way It Began…” — plotted by Lee, but scripted and penciled by his younger brother, Larry Lieber, and inked by Paul Reinman — from Tales of Suspense #53.(May, 1964).

published years earlier. That included this first installment which, much like the lead story of this issue, presented the origin of its star through a flashback sequence narrated by that character. The thirteen-page “The Wonder of the Watcher!” — scripted by Lee, penciled by Gene Colan, and inked by Syd Shores — was, therefore, a direct adaptation of the five-page “The Way It Began…” — plotted by Lee, but scripted and penciled by his younger brother, Larry Lieber, and inked by Paul Reinman — from Tales of Suspense #53.(May, 1964).

As with the Silver Surfer and Galactus, I was probably already at least a little familiar with the Watcher, even if I’d never read a comic book story featuring him before, through having seen him on the Fantastic Four TV cartoon. At minimum, I would have been cognizant of his basic deal — that he was extremely powerful and knowledgeable, and sympathetic to humanity, but forbidden somehow from taking any kind of active role in helping us out — though, thankfully for the Fantastic Four and their fellow Marvel heroes (not to mention the rest of the planet), he usually found a way to circumvent, if not outright break, the rules.

As with the Silver Surfer and Galactus, I was probably already at least a little familiar with the Watcher, even if I’d never read a comic book story featuring him before, through having seen him on the Fantastic Four TV cartoon. At minimum, I would have been cognizant of his basic deal — that he was extremely powerful and knowledgeable, and sympathetic to humanity, but forbidden somehow from taking any kind of active role in helping us out — though, thankfully for the Fantastic Four and their fellow Marvel heroes (not to mention the rest of the planet), he usually found a way to circumvent, if not outright break, the rules.

As noted above, this retelling of the Watcher’s origin runs thirteen pages, whereas the original tale it’s based on ran only five. Lee and Colan don’t really add any significant plot details to the Tales of Suspense version, but rather take advantage of the extra page count to let the story stretch out and breathe — and to allow Colan and Shores to shine in producing full-page splash panels like this one, three pages in:

Jack Kirby’s original visualization of the Watcher in 1963 had given him an oversize, somewhat blocky-looking head, and a relatively lean body. He’d beefed him up in the intervening years, adjusted his proportions, and rounded off his cranium as well — but Colan’s version, as showcased here, is probably as close as the character would ever come to looking like a conventional Marvel superhero.

Jack Kirby’s original visualization of the Watcher in 1963 had given him an oversize, somewhat blocky-looking head, and a relatively lean body. He’d beefed him up in the intervening years, adjusted his proportions, and rounded off his cranium as well — but Colan’s version, as showcased here, is probably as close as the character would ever come to looking like a conventional Marvel superhero.

From here, the story moves directly into the flashback sequence that comprises the rest of the tale. It’s interesting to note how much its beginning, at least, parallels that of the Surfer’s flashback to Zenn-La — for like the former herald of Galactus, the Watcher originally hails from an ancient world whose inhabitants had, many ages past, achieved a Utopian level of peace, prosperity, and technological advancement:

Unlike the Zenn-Lavians of Norrin Radd’s time, however, the race of humanoids destined to become the Watchers were anything but content with their paradise:

Their decision having been made, the members of the High Tribunal — including the dissenter Emnu — absorbed “cosmic anti-matter isotopes” which transformed their bodies into living energy:

The Prosilicans gladly accepted the strangers’ offer, and soon they had learned enough to build their own cyclotron:

Changing back into their pure energy forms, the Watchers-to-be embarked on a scenic tour of the cosmos. But on Prosilicus, things soon went terribly wrong. One of their leaders decided to apply their new technology to build nuclear weapons, and others soon followed suit. Before long, nuclear war broke out, devastating much of the planet.

Here Lee and Colan introduce the most significant change in their version of the story; for while the Prosilicans in Lee and Lieber’s original tale only destroy themselves, in this telling they also mange to launch nuclear warheads against their neighboring planets…

…with the result than not one, but two world civilizations are completely destroyed:

The ending of the story, however, is very much the same:

It’s a good story, in either version, though the more expansive rendition by Lee and Colan must be considered the definitive one. It provides a credible as well as a dramatic reason for the Watchers’ creed of noninterference, and has continued to be an influential part of Marvel Universe lore through the decades — such as in 2014’s Original Sin #0 (written by Mark Waid and penciled by Jim Cheung and Paco Medina), where, in a moving sequence, the young superhero Nova discovers that in the Watcher’s incessant monitoring of the multiverse (the conceptual basis of Marvel’s What If? series of the 1970s and later), he continues to look for a single reality in which things turned out differently on Prosilicus:

Since young Sam Alexander (Nova) grew up doubtful of his father’s claims to have once been a member of the interstellar Nova Corps, he can relate to the Watcher’s “daddy issues”, making for a poignant scene.

Of course, as many of this blog’s readers will already know, the Watcher perishes during the course of the Original Sin limited series/crossover event, so it seems even more unlikely now that he’ll ever be successful in his quest. On the other hand, it’s hard to imagine that a character with as long and rich a history in the Marvel Universe as Uatu, the Watcher, is really gone for good.

But while we may not know what’s coming next for the Watcher, if anything, there’s little doubt where he’s come from. The character initially appeared in Fantastic Four #13 (April, 1963) and is generally considered to be a creation of Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. So is Galactus; and so, for that matter, are the FF themselves.

The Silver Surfer is different.

Jack Kirby, while drawing Fantastic Four #48 — the first chapter of what fans would soon be respectfully calling the “Galactus Trilogy” — from the basic plot that he and Stan Lee had worked out, decided to throw in a new character he and Lee had not discussed — a herald for Galactus, depicted as silver alien riding a surfboard in space. Lee had no idea who the character was when the penciled pages showed up at the Marvel offices. This sequence of events has been attested to by several individuals who should know, including Lee himself, and is not in dispute.

The Surfer arrives on Earth in FF #48, but gets knocked off a roof by the Thing before he has a chance to utter a word. In the next issue, however, we find that he’s landed (by a most convenient coincidence) atop the skylight of the apartment of the Thing’s blind girlfriend, Alicia Masters. She brings him in — and it’s in this scene that Lee first puts words in the mouth of Kirby’s creation:

The word “nobility” has not meaning to the Surfer? Gee, that doesn’t sound much like Norrin Radd.

Nor does the Surfer’s sudden discovery of the meaning of “beauty” — “a word some races use” — square up at all with the anguished pinings for “the lovely, faithful Shalla Bal” we encounter in Silver Surfer #1.

It seems clear that, in Kirby’s original conception — and in Lee’s initial interpretation of it, as well — the Silver Surfer was intended to be a wholly alien being. One whose nobility is based more on his complete, childlike innocence than on anything he’s actually done, or even thought. The Surfer we meet here isn’t the same individual as the one who sacrifices his own happiness so that his world can live, and then dedicates himself to finding worlds bereft of intelligent life for his master to consume. This is a being who doesn’t discover his conscience until it’s been awakened in him by his contact with humanity — as he explains to Galactus in FF #50:

Exiled to Earth by Galactus at the end of this issue, the Surfer leaves the Fantastic Four behind to explore his new home. But by FF #55, he’s already seen plenty — maybe too much, as he explains to his best pal Alicia:

By the time he scripted this story, Stan Lee had seen the reader response to the Surfer’s earliest appearances, and knew he had a new character sensation on his hands. It’s possible, as some have suggested, that he saw the Surfer as a potential vehicle for addressing the spiritual yearning that was a growing part of the zeitgeist of the Sixties, especially among the college-age audience he sought to cultivate. As he told Jon B. Cooke in a 2001 interview for The Jack Kirby Collector #33, “I liked the way Jack drew him [the Surfer] very much; there was a certain nobility to his demeanor, so I tried to write him as though he was a somewhat spiritual guy.” In any event, Lee began having the Surfer “deliver remarks about the condition of life on Earth and how we don’t appreciate this Garden of Eden we live in” (Lee again, quoted in Les Daniels’ Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World’s Greatest Comics, 1991).

Writing the Surfer this way, it may have seemed a natural progression to Lee to develop the Zenn-Lavian backstory for the character — to establish him as a human being (if not an Earthling) who was noble and selfless before he ever met Galactus. Perhaps he didn’t even realize that the origin story that he and John Buscema put together for Silver Surfer #1 obviously contradicted what he and Jack Kirby had established about the character in Fantastic Four. But the fans realized it — some of them, at least — right away.

In Silver Surfer #4, Lee published a letter from reader Evan Katten which outlined what Katten called “a few problems that have existed since the Surfer’s origin”, and then casually provided tidy explanations for all of them. According to Katten, after transfiguring Norrin Radd into the Silver Surfer, Galactus made his herald gradually forget both his human emotions and his dedication to preserving life. “Thus although it was a feeling Surfer who left his world, it was a cold, inhuman one that reached Earth.” His conversations with Alicia Masters didn’t awaken his compassion for the first time, but, rather, helped to restore it.

In Silver Surfer #4, Lee published a letter from reader Evan Katten which outlined what Katten called “a few problems that have existed since the Surfer’s origin”, and then casually provided tidy explanations for all of them. According to Katten, after transfiguring Norrin Radd into the Silver Surfer, Galactus made his herald gradually forget both his human emotions and his dedication to preserving life. “Thus although it was a feeling Surfer who left his world, it was a cold, inhuman one that reached Earth.” His conversations with Alicia Masters didn’t awaken his compassion for the first time, but, rather, helped to restore it.

The talented comics storyteller and Kirby acolyte Tom Scioli, in an in-depth critique of Silver Surfer #1 for The Comics Journal, calls Katten’s letter an example of “the crowdsourcing of Marvel’s mythology that Stan the Editor encouraged in his letter columns and Bullpen Bulletins”, and he’s right, of course. When readers would write in complaining about story errors, Lee would promise them a “No-Prize” if they could provide a reasonable explanation for what only appeared to be an error — if they’d dig Lee and company out of the hole they’d dug for themselves, in other words. There were no editorial responses to any of the letters published in SS #4, Katten’s included, but you’ve got to hope that they slipped the guy a No-Prize in the mail, anyway. After all, this is  almost exactly the version of the Surfer’s history that Marvel’s writers would invoke in the years and decades to come — as in this sequence by Jim Starlin (writer) and Ron Lim (penciler) from Silver Surfer (1987 series) #48 (April, 1991):

almost exactly the version of the Surfer’s history that Marvel’s writers would invoke in the years and decades to come — as in this sequence by Jim Starlin (writer) and Ron Lim (penciler) from Silver Surfer (1987 series) #48 (April, 1991):

So — if our only concern is with continuity, there’s no longer problem with the conceptual dissonance that Stan Lee and John Buscema inflicted upon the character in Silver Surfer #1. But that’s not our only concern — or, at least, it shouldn’t be.

Because Jack Kirby created the Silver Surfer, in 1966. And he had a specific conception for the character, even if it wasn’t (at least at the beginning) an elaborate origin story of the sort that Lee and Buscema crafted two years later. As Kirby would relate in a number of interviews, beginning in 1970 or thereabouts, his vision of the Surfer was derived from his conception of Galactus — which was that the eons-old destroyer of worlds was, essentially, God — or at least a close approximation thereof:

When I drew Galactus, I just don’t know why, but I suddenly figured out that Galactus was God, and I found that I’d made a villain out of God, and I couldn’t make a villain out of him. And I couldn’t treat him as a villain, so I had to back away from him. I backed away from Galactus, and I felt he was so awesome, and in some way he was God, and who would accompany God, but some kind of fallen angel? And that’s who the Silver Surfer was. And at the end of the story, Galactus condemned him to Earth, and he couldn’t go into space anymore. — San Diego Golden State Comic Con panel, 1970.

But the Surfer wasn’t just any fallen angel. As Kirby explained to Mark Borax in 1986 for the 41st issue of Comics Interview, “I got the Silver Surfer, and I suddenly realized here was the dramatic situation between God and the Devil! The Devil himself was an archangel. The Devil wasn’t ugly – he was a beautiful guy! He was the guy that challenged God.”

The Silver Surfer is the Lucifer to Galactus’ God, in other words. And while Stan Lee’s conception of the Surfer also draws on Judeo-Christian religious symbolism, the figure that Lee based his Surfer on wasn’t Lucifer, but rather, Jesus Christ — a righteous figure of purity, who suffers for the sins of humanity. Even if you frame Kirby’s conception of the Galactus-Surfer relationship as a sort of inversion or mirror image of the “real” religious story, or myth — with “God” as the villain, and “the Devil” as the hero of the story — it’s still quite the cognitive leap from Lucifer to Christ. They’re very different symbols.

The Silver Surfer of Jack Kirby and the Silver Surfer of Stan Lee are in fact so different that many fans have come to think of them as separate characters — and that includes some who prefer Lee’s version, as well as those that believe Kirby’s is the only “true” version of the character. But whichever Surfer you prefer, it seems to be incontrovertible fact that Kirby had intentions for the Surfer that were never realized, due to Lee’s taking the character off his hands.

According to Mark Evanier’s Kirby: King of Comics (2008), the artist was already working on the plot for a Fantastic Four storyline that would fill in details of the Surfer’s background when he learned that Lee was preparing to launch a new Silver Surfer title, to be drawn by John Buscema, and that the first issue — already in the works — would present their version of the character’s origin. Kirby was forced to scrap his plot and (according to Evanier) some pages he’d already penciled (though it seems likely, simply based on the time-frame, that some part of his planned storyline may have found its way into FF #74 – #77 — a four-part arc which featured the return of Galactus, and whose last chapter, as already noted, came out the same month as Silver Surfer #1).

According to Mark Evanier’s Kirby: King of Comics (2008), the artist was already working on the plot for a Fantastic Four storyline that would fill in details of the Surfer’s background when he learned that Lee was preparing to launch a new Silver Surfer title, to be drawn by John Buscema, and that the first issue — already in the works — would present their version of the character’s origin. Kirby was forced to scrap his plot and (according to Evanier) some pages he’d already penciled (though it seems likely, simply based on the time-frame, that some part of his planned storyline may have found its way into FF #74 – #77 — a four-part arc which featured the return of Galactus, and whose last chapter, as already noted, came out the same month as Silver Surfer #1).

By all accounts, Kirby was extremely unhappy at this turn of events. As he world put it in 1971 — not long after leaving Marvel — “There were times at Marvel when I couldn’t say anything because it would be taken away from me and put in another context, and it would be lost – all my connection with it would be severed. For instance, I created the Silver Surfer, Galactus and an army of other characters, and now my connection with them is lost… You could devote your time to a character, put a lot of insight into it, help it evolve and then lose all connection with it.” He expanded on his original intentions for the Surfer on another occasion**, saying: ““I meant to round out the Silver Surfer, give him his own motivation, which has never been clear… I felt there was real meaning to

the Silver Surfer. He is a character with a lot of power and that power was never really exploited.”

I should point out here that there’s no evidence (at least, none that I’ve turned up in my research) that Kirby expressed his displeasure to Lee over the handling of the Surfer at the time this all was happening. And it’s entirely possible that Lee didn’t comprehend how much the character actually meant to his most important creative partner. Kirby was already drawing three books full-time — Fantastic Four, Thor, and Captain America — and would have almost certainly had to surrender one of those to add Silver Surfer to his schedule. Perhaps Lee simply assumed that Kirby would prefer to keep working on those older, better-established features, if so, it’s unfortunate that he appears never to have thought to ask his colleague if this was indeed the case.

And thus, this final panel of the Surfer in FF #77 — ironically footnoted with Lee’s plug for Silver Surfer #1, then on sale — would be the last time that Kirby would draw his iconic creation within the pages of the comic book series for which he’d first imagined him, Fantastic Four.***

And thus, this final panel of the Surfer in FF #77 — ironically footnoted with Lee’s plug for Silver Surfer #1, then on sale — would be the last time that Kirby would draw his iconic creation within the pages of the comic book series for which he’d first imagined him, Fantastic Four.***

And thus, one more brick was laid in the wall of disenchantment that was growing between Kirby and the House of Ideas that he had done as much, if not more, than anyone else to build. Disenchantment that would lead him to put less and less of himself into the work he continued to turn out for Marvel — to keep his most original ideas to himself — and, in two years’ time, to jump ship for Marvel’s number one competitor, DC Comics.

And that, dear readers, is why it’s not really possible for me to take Stan Lee and John Buscema’s “The Origin of the Silver Surfer” purely on its own terms — as much as my inner ten-year-old might wish I could.

Considering how long this post has turned out to be, you might think I’ve said all there is to say on the subject of the Silver Surfer series, but that’s not quite true. After all, there are another two years worth of comics — seventeen more issues — yet to come. And while I didn’t buy every single issue — not by a long shot — I did buy several, and I’ll be posting about them here. I mean, Silver Surfer #4 has got to be one of my top four or five comic books of the 1960s. There’s no way I’m not writing about that one, y’all.

Considering how long this post has turned out to be, you might think I’ve said all there is to say on the subject of the Silver Surfer series, but that’s not quite true. After all, there are another two years worth of comics — seventeen more issues — yet to come. And while I didn’t buy every single issue — not by a long shot — I did buy several, and I’ll be posting about them here. I mean, Silver Surfer #4 has got to be one of my top four or five comic books of the 1960s. There’s no way I’m not writing about that one, y’all.

But I’m glad to announce that this is the last time I’ll write about Jack Kirby prior to writing about a comic book he actually drew. In case you haven’t noticed, my younger self is now about five months in as a regular Marvel Comics reader, and he still hasn’t bought a Jack Kirby comic. That will soon change.

Something to look forward to, right?

*For the record — those titles were Ghost Rider, Not Brand Echh, and Captain Savage and His Leatherneck Raiders. Marvel Super-Heroes, which by 1968 was a title that featured new material as well as reprints, had begun in 1966 as the all-reprint Fantasy Masterpieces.

**I have no date for this quote, but it’s included in Will Murray’s retrospective, “The Formative Fantastic Four”, in The Jack Kirby Collector #54.

***It wouldn’t be the last time Kirby would draw the Surfer for a Marvel comic, of course — or even as part of a collaboration with Lee — but that’s a story for another post.

This was a really interesting read. I was born in 1976, and began reading comic books around 1983. So for a very long time as far as I knew the Silver Surfer had always been Norrin Radd, who agreed to serve as the herald of Galactus in order to save Zenn-La.

It wasn’t until quite a number of years later, the late 1990s at the earliest, or maybe the early 2000s, that I finally learned that Jack Kirby had created the Silver Surfer completely on his own, without any input from Stan Lee, that he had his own completely different origin for the character, and that he was disappointed to learn that Lee, working with John Buscema, decided to devise a completely different backstory for the character, thereby preventing Kirby from telling the story he had intended to tell.

I really do not want to turn this into a Lee versus Kirby comment. I believe that both men played extremely vital roles in the mammoth success of Marvel Comics. However, at the same time, it does become apparent why their partnership could not last indefinitely. I’ve heard Lee and Kirby likened to the Beatles, and Kirby’s departure from Marvel compared to the break-up of the band. When you have two extremely strong-yet-different creative voices like Lee and Kirby, it probably becomes inevitable that eventually their partnership can no longer endure, because each of them has a different idea of where they want to go next.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ben, I couldn’t have put it better myself.

LikeLike

I’m glad you asked the same question I’ve long been wondering myself; I can just imagine Norrin asking Galactus “What’s a Surfer?” The in-universe reason is a puzzle that maybe not even Evan Katten could answer; out-of-universe Jack obviously noted that surfing had become trendy by mid-’60s.

Some typos:

“never to venture fourth again.” s/b

“never to venture forth again.”

“emporarily slipping” s/b

“temporarily slipping”

“Shalla Ball” s/b

“Shalla Bal”

“wherei” s/b

“where”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Typos fixed, Pat. Thanks!

LikeLike

I remember being sooo disappointed when I bought Silver Surfer #1. I was a big fan of John Buscema, but the Silver Surfer was a Kirby carchater!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I bought Silver Surfer #1 off a news stand when it first came out all those many years ago. I guess I liked it. I bought the next four issues of Silver Surfer, but I quit buying it after issue #5. I can’t remember exactly what it was that lead me to quit buying the comic book. It just wasn’t a comic book I wanted to buy. The 1968 series was cancelled after 18 issues which was a pretty short run. It had to be a serious blow to Stan Lee and Marvel to have a comic book that was launched with such fanfare flop so badly. It looked to me that John Buscema was trying to copy Jack Kirby. John Buscema was a very talented artist in his own right and he did do a good Kirby imitation, but he wasn’t Jack Kirby. The story I’ve read is that Stan Lee back in the day wanted all his artists to copy Jack Kirby. Don Heck was supposed to have told Stan Lee that if he wanted Jack Kirby, he should get Jack Kirby.

Things had clearly changed at Marvel by 1968 from the early 1960’s. From 1961 to the end of 1965, Jack Kirby was involved in some way with the launch of virtually every new Marvel Series. Fantastic Four, the Incredible Hulk, the Mighty Thor, Antman, Iron Man, Avengers, Uncanny X-Men, Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos, the revival of Captain America, and Nick Fury, Agent of Shield all had Jack Kirby’s heavy involvement. The only exceptions were Doctor Strange, Daredevil and probably Spider-man (although Jack Kirby drew the original Spider-man cover). Things changed in 1966. For a five month period from December, 1966 to April, 1967 (by release dates), Jack Kirby only did the art for Fantastic Four and Mighty Thor after a long period where he did the art or the story layouts or the cover art for several series for Marvel.

Looking back, it is regrettable that Jack Kirby was not involved with the launch of Silver Surfer. Silver Surfer was his creation but it would take time to fully develop the character. He didn’t get that opportunity. It is clear that by 1968, the well was poisoned at Marvel.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Joshua, thanks for stopping by, and for taking the time to comment! I also dropped Silver Surfer after #5 (although I actually missed both #2 and #3, as I’ve written about elsewhere on the blog) — but I came back for the final, Kirby-drawn issue, #18. I’ll be posting about that one next month.

LikeLike