If you’ve ever read this blog, the cover of Detective #354 should already be familiar to you. There it is, proudly displayed in the header above every post. (UPDATE: The original header was retired in May, 2020, but can still be accessed via the link given above.) Obviously, I have a lot of affection for this particular offering from the team of Carmine Infantino and Joe Giella, who contributed so many classic covers to this era of Batman comics (and even got to sign this one — not a routine occurrence at the time).

In some ways, it’s a head-scratcher that the cover is as effective as it is. A dozen or so thugs — none of them especially formidable-looking — are depicted standing in a half-circle around Batman, shaking their fists at him. The cover copy describes this as “The Caped Crusader’s most dangerous trap”. Really? Even in 1966, and even without taking the then-insanely-popular TV show’s weekly cliffhangers into consideration, I believe my eight-year-old self must have been skeptical of that claim. Sure, the odds are against him, but he’s Batman. These hoods aren’t even armed. Even if he’s not able to take them all down, our hero should at least be able to break free of this “most dangerous trap” and escape. And while those “force lines” drawn around the thugs’ brandished fists may be intended to make them look more threatening, the actual effect comes off as just a little bit silly.

Nevertheless, this cover works some kind of strange magic on me, even after fifty years. Part of it. I’m sure, is the symmetrical simplicity of the design, with Batman standing in a spotlight in the center of the semi-circle of foes. Then there’s the color scheme, with the red and yellow-orange background hues contrasting effectively with the blue and gray of Batman’s costume at front and center. But I think the most important element is the figure of Batman himself, drawn by Infantino as poised and ready to throw himself into action at any moment — stationary, but with the sweep of the cape giving an illusion of arrested motion (as well as playing into the cover’s overall circular compositional structure) — with the slight sneer on Batman’s face indicating his contempt for his foes, as well as his determination to fight his way free.

All in all, it’s a relatively restrained cover — at least in comparison to the absolutely bonkers, all-in-on-“camp” cover of Justice League of America #46 — an issue that came out in the same month as Detective #354, and about which I posted just a few weeks ago. It seems that editor Julius Schwartz may have believed that Batman’s own books would probably sell without the covers resorting to a lot of gimmickry, but comics that merely featured Batman as one hero among many (and didn’t have his name or logo in or near the title, like Detective did) needed extra “help”.

Whether or not that’s true, the cover of Detective #354 is undoubtedly a memorable one; alas, the story it promotes is not quite in the same league. “No Exit for Batman!”, by John Broome, Sheldon Moldoff, and Giella, is most notable (if that’s the right word) for being the first tale to feature Dr. Tzin-Tzin — “Batman’s newest arch-villain”, as the cover blurbs him. If, however, you look at the cover’s inset illustration of the good doctor and think, “Oh, just another Fu Manchu knock-off”, well,  you’re not too far off. Not that such stereotypical, “yellow peril”-evoking Asian criminal masterminds were anything new for Detective Comics — you only have to look at the cover of the first issue, as shown at left, to verify that.

you’re not too far off. Not that such stereotypical, “yellow peril”-evoking Asian criminal masterminds were anything new for Detective Comics — you only have to look at the cover of the first issue, as shown at left, to verify that.

And indeed, our first view of Dr. Tzin-Tzin in the story, in a scene which depicts him driving a henchman to death by fright simply by staring into his eyes in a hypnotic manner, is likely to reinforce the impression of the character as an example of the racially insensitive Fu Manchu villainous archetype. As is Commissioner Gordon’s telling Batman and Robin of Tzin-Tzin’s committing incredible “super-crimes” all over the world. But, as it turns out, there is a bit of an unexpected twist to the sinister doctor’s background, as Gordon also relates to the Dynamic Duo:

Get it? Dr. Tzin-Tzin isn’t simply a new riff on Fu Manchu, because he’s not even really Chinese (or any other kind of Asian)! He’s “American”! By which Gordon means, obviously, that Tzin-Tzin is of white European descent.

Yes, the mid-1960s were an era when DC would frequently publish single-page comics PSAs that were obviously sincere paeans to brotherhood and tolerance — not to mention classic stories devoted to the same themes, such as “Indestructible Creatures of Nightmare Island!” — but they were also an era when it would never occur to its creators or editors to question the assumption that the normative baseline for “American” equated to “white person”.

And in case you think that maybe the Commissioner’s wording is vague enough to give Broome some wiggle room, a quick look at how Dr. Tzin-Tzin is rendered (and colored) within the story — as opposed to the cover, where his slant-eyed profile sports the same yellow-orange hue used as one of the two background colors — should dispel that notion:

No, set aside the “traditional” Chinese clothing and hairstyle, and it’s evident that Dr. Tzin-Tzin is about as Asian (at least genetically speaking) as the film Iron Man 3‘s Mandarin, Trevor Slattery.

Moving on to another topic, the “gory fist battle”, as one of Tzin-Tzin’s henchmen calls it in the panel above, is of course the big fight promised by the cover — but since this is a 1966 Code-approved comic, there’s no blood to be seen anywhere, though there are of course plenty of the onomatopoeic sound effects that were de rigueur for a Batman comics story at the time. As for it being Batman’s “most dangerous trap” — well, the Caped Crusader does take quite a bit of punishment, but he gives as good as he gets, and at the end of the scuffle he’s still on his feet, as he watches the fleeing thugs scatter into the night.

As it turns out, Dr. Tzin-Tzin doesn’t have a lot to threaten our heroes with beyond his hired muscle. Once the Dynamic Duo catch up with him, the faux Asian mastermind tries to work his stare-of-fear trick on Batman, but the hero deduces that his foe’s hypnotic powers are magnified by a special light shining from behind him, and smashes the source with a backwards-tossed batarang. Then Batman punches Dr. Tzin-Tzin through a doorway — and that’s that. So much for “Batman’s newest arch-villain”.

As I was preparing to write this post, I couldn’t remember if Dr. Tzin-Tzin had ever made any further appearances, and if so, where. I was somewhat surprised to discover (courtesy of Mike’s Amazing World and other sources) that he’d had a longer and more visible career than I’d recalled. His very next  appearance, in fact, is a minor classic of sorts, due primarily to the stellar artwork of Neal Adams. It’s frankly tempting to write more about that tale (which appeared in Detective #408) here — it’s a better story — but I’ve decided to refrain from such until it becomes eligible for its own 50-year-old-comic post in December, 2020. For now, I’m going to limit myself to sharing the story’s wonderfully macabre cover (seen at right), and also to noting that it introduced an association between Dr. Tzin-Tzin and Ra’s al Ghul‘s League of Assassins.

appearance, in fact, is a minor classic of sorts, due primarily to the stellar artwork of Neal Adams. It’s frankly tempting to write more about that tale (which appeared in Detective #408) here — it’s a better story — but I’ve decided to refrain from such until it becomes eligible for its own 50-year-old-comic post in December, 2020. For now, I’m going to limit myself to sharing the story’s wonderfully macabre cover (seen at right), and also to noting that it introduced an association between Dr. Tzin-Tzin and Ra’s al Ghul‘s League of Assassins.

For better or for worse, Tzin-Tzin’s faux-Asian status seems to have been ignored in this as well as in his later appearances, which found the villain going up against Supergirl, Jonny Double, and the Peacemaker as well as Batman. Dr. Tzin-Tzin finally dropped out of sight in the late Eighties, and has remained unseen ever since, save for one brief cameo in 2012’s Batman Incorporated #4 — courtesy of writer Grant Morrison, who never met an obscure Bat-villain he didn’t like. Whether the fiendish doctor will return to bedevil Batman and his allies in the post-“Rebirth” DC universe remains to be seen, of course. (I wouldn’t hold my breath in anticipation, but I wouldn’t lay odds against it ever happening, either.)

The second story in Detective #354 was the latest installment in the adventures of Ralph Dibny, the Elongated Man, who at this point had been holding down the back-up slot in Detective for a little over two years, ever since the “New Look” began in issue #327. In the months since our last check-in with the Stretchable Sleuth (in #344), a couple of changes had come to the feature — Ralph had begun sporting a new red, black, and yellow costume in #350, and the character’s co-creator and regular artist, Carmine Infantino, had also begun inking his own pencils with the issue before that. My eight-year-old self was fine with the costume switch, as I recall, but was less happy with the change in the strip’s look. Then and now, I prefer Infantino’s pencils when embellished by a smoother, more finely detailed inker such as Sid Greene or Murphy Anderson (though I expect that there are plenty of Infantino fans who’ll disagree with me on that one).

“The Double-Dealing Jewel Thieves!”, written by John Broome, is a typical Elongated Man tale, in which Ralph and his wife Sue investigate a mystery involving not one, but two masterfully forged replicas of the Crown Jewels of England, ultimately leading to the recovery of the true royal treasures, which have been cunningly spirited out of the Tower of London unbeknownst to anyone. It’s a minor but enjoyable story, whose most notable flaw is that it spends so much time explaining how the thieves double-cross each other with their multiple fakes that it never gets around to telling us how they managed to nab the world’s best-guarded jewels in the first place — but hey, you can’t have everything in one 10-page story.

The main thing that struck me while re-reading this story in 2016, however, is how distinctively the hero’s stretching ability is depicted in these mid-Sixties tales, particularly in comparison with two other well-known superheroes sharing essentially the same power set — Plastic Man and Mister Fantastic.

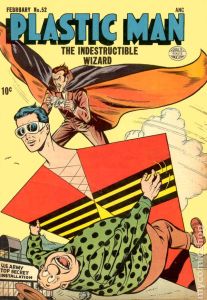

Plastic Man is, of course, the first of the stretchable superheroes,

Plastic Man is, of course, the first of the stretchable superheroes,  having been created by writer-artist Jack Cole for Quality Comics in 1941. Cole (as well as most others who’ve worked on the character, such as Kyle Baker) saw the potential of his hero’s powers as a vehicle for surreal humor — and so the reformed criminal Eel O’Brien became a virtual shape-shifter, forming himself into red, black, and yellow replicas of all kinds of objects and creatures. His malleability, as well as his ability to increase or decrease his mass, appeared to have no definable limits, and so his original human form came to seem no more “natural” than any other he might assume.

having been created by writer-artist Jack Cole for Quality Comics in 1941. Cole (as well as most others who’ve worked on the character, such as Kyle Baker) saw the potential of his hero’s powers as a vehicle for surreal humor — and so the reformed criminal Eel O’Brien became a virtual shape-shifter, forming himself into red, black, and yellow replicas of all kinds of objects and creatures. His malleability, as well as his ability to increase or decrease his mass, appeared to have no definable limits, and so his original human form came to seem no more “natural” than any other he might assume.

In contrast, Marvel Comics’ Mister Fantastic — created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby as a member of the Fantastic Four in 1961 (thus making him a close contemporary of the Elongated Man, who debuted in 1960’s Flash #112) — was a sober-minded scientist, Reed Richards, whose powers could be seen as a metaphor for his expansive, probing intelligence, and thus were rarely played for laughs (the

In contrast, Marvel Comics’ Mister Fantastic — created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby as a member of the Fantastic Four in 1961 (thus making him a close contemporary of the Elongated Man, who debuted in 1960’s Flash #112) — was a sober-minded scientist, Reed Richards, whose powers could be seen as a metaphor for his expansive, probing intelligence, and thus were rarely played for laughs (the  occasional exceptions being the wisecracking observations of his teammate, the Thing). Still, his malleability was on a par with that of Plastic Man, with his whole body — bone, blood, muscle, skin, and so on — all seemingly made of the same endlessly pliable substance. For Reed Richards, as for Eel O’Brien, human anatomy seemed to count as little more than a convenient “at rest” state.

occasional exceptions being the wisecracking observations of his teammate, the Thing). Still, his malleability was on a par with that of Plastic Man, with his whole body — bone, blood, muscle, skin, and so on — all seemingly made of the same endlessly pliable substance. For Reed Richards, as for Eel O’Brien, human anatomy seemed to count as little more than a convenient “at rest” state.

Ralph Dibny was plenty pliable as well, of course, and he pulled many of the same moves as Eel and Reed — but Broome and Infantino never forgot that their hero was the Elongated Man. More than any other stretchable hero of whom I’m aware, Ralph was inclined to elongate, inflate, or otherwise transform specific parts of his body. There are a couple of great examples of this in Detective #354, including this one:

Why go all Pinocchio on the bad guy when an elongated arm could have planted a fist on him just as easily? Well, why not?

And from a little earlier in the story, an even more bizarre instance:

The effect of the hero’s rubbery arm and fist emerging from a luxuriant mass of red hair may not be quite as hilarious as those generated by Plastic Man’s wacky shape-changing antics, but it’s equally surreal, at least to my mind.

This propensity for anatomical exaggeration — evident in many other tales from this era of the Elongated Man, as well as in this one — distinguishes the hero from his pliable peers in a way that had never occurred to me prior to my re-reading “The Double-Dealing Jewel Thieves!” for this post (or, if it had, I’d long forgotten it). It’s a small thing, of course — but after reading about a character for over fifty years, it’s a pleasure to realize one can still discover something new.

Ralph had it all over Reed when it came to the visuals of stretching. Small wonder Infantino listed it as one of his favorite strips to work on.

LikeLiked by 1 person